Pinochet's legacy: an ironclad extractivist regime

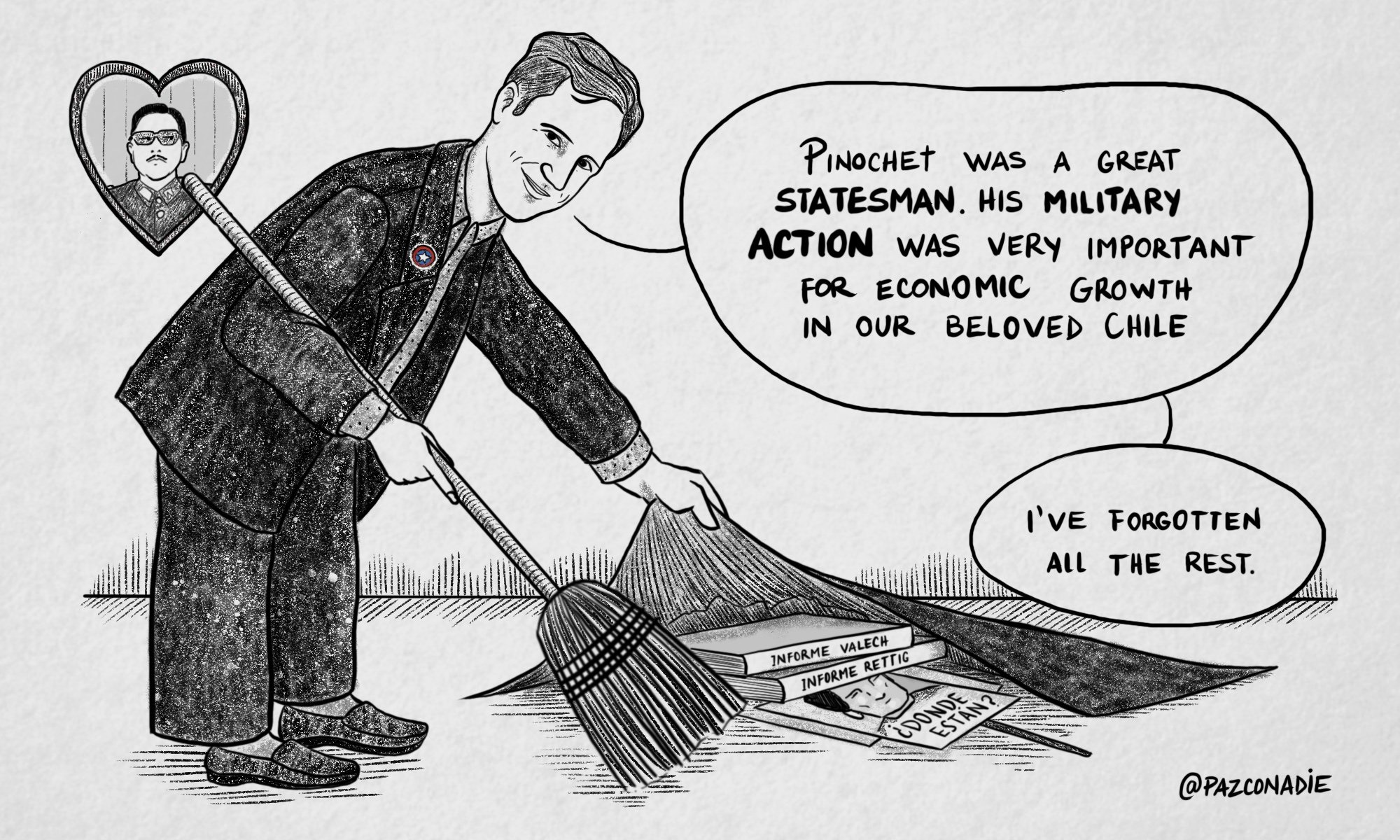

Luis Silva of Chile’s Republican Party is one of many on the right who justify the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Drawing by @PazConNadie.

Opinion • Fany Lobos Castro • September 14, 2023 • Leer en castellano

Fifty years after the military coup in Chile, it feels like the intention is to close a cycle, to turn the page, and to lead us to believe we’ve left the past behind.

The media and commemorative events fragment the stories that surround this historical milestone. Official discourse favours memorable speeches that highlight certain aspects and avoid others, perpetuating a narrative that avoids pointing out obvious responsibilities.

Despite this, we feel more strongly than ever—as do the territories we live on—that the structures, laws and dynamics of the dictatorship did not disappear with Augusto Pinochet.

Chile’s oligarchic political class upholds a legacy of repression, as if machine guns still echoed in the seat of government at La Moneda. The link between the coup and neocolonial dynamics of capital accumulation cannot be ignored.

During the 17 year dictatorship, the Chilean State crafted a legal framework to ensure the exploitation and control of, and access to, natural resources. Examples abound: the 1980 Political Constitution, the 1981 Water Code, the 1982 Electricity Transmission Law and the 1983 Mining Code. It was then that the wheels were set in motion for the installation of large transnational corporations in Chile, which became the first Latin American country to establish a neoliberal extractivist model that would go on to function as a model for the rest of the continent.

We could fill pages and pages with the abuses that have taken place, and continue to take place, in Chile. The dictatorship led by Pinochet represented rupture in the political history of Chile, as well as the reestablishment of the country's economic and social structures in the hands of the richest families. These families do not hesitate to use their bloodlines and wealth to monopolize everything possible so as to remain in power.

As is to be expected, it is these families have shaped the policies of the governments that followed dictatorship, be they to the right or to the left. Today, in this country "of progress," people are going into debt to be able to eat.

The extractivist dictatorship

After 1973, the implementation of neoliberal policies and institutions produced an extractivist machinery that declared war on nature. I live in a rural, dispossessed and precarious territory on the lower slopes of the Andes, the kind that not many care about. But the south-central region of Chile has been in the news more and more because of disasters such as the massive summer fires that razed our mountain forests. These fires also end up benefiting big forestry companies. In the winter, we experience flooding every other week. Those who lose their homes are campesinos and people living on the peripheries of cities, in a region that holds four large water reservoirs for logging companies and large swaths of lands dedicated to agribusiness.

These increasingly frequent disasters aren't natural, they too are a legacy of the dictatorship. This is part of why we must interrogate what remembering fifty years since the coup means.

We share the pain and frustration for the losses of our compañeros and compañeras that have gone half a century without truth or justice, and who are only remembered around the dates of the anniversary of the coup. But there is also rage at the failure of these commemorations to make visible capitalism and the market.

The privileged in our country or in rich nations in Europe, the U.S. or China, aren’t the only ones who reap the benefits of transforming life into a commodity. Political parties in Chile—across the political spectrum—do as well, and in doing so, they knowingly and intentionally perpetuate the legacy of the dictatorship.

The selective focus of the coup commemorations are centered on prominent citizens, politicians, artists, unionists or soldiers, which means the anonymous struggles of campesino, rural, neighbourhood and women's movements are pushed into oblivion. These movements not only defied the dictatorship back then; they’re active today and continue to fight Chile’s deep inequality.

Omitting these voices and struggles from the commemoration of the coup silences an essential part of our history and in doing so, suggests that change can only come from the elites in power.

In this context, it's essential to recall the forms of organization that led to urban land occupations, in which communities, lacking money and legal permits, were able to guarantee a place to live collectively.

We remember the ollas populares (communal meals) prepared for the most part by women in times of hunger, and how small farmers organized to feed those branded as "reds" for demanding agrarian reform. These autonomous initiatives, among many others, manage to sustain life without depending fully on the state or capital.

Our memory includes the knowledge of community organizing, neighbourhood assemblies and the simple action of "parar la olla," as we say in this region: to feed the community through neighborly solidarity and mutual aid.

It's true that the so-called "shock therapy," which was applied through unimaginable levels of violence and cruelty, allowed Chile’s elites to implement unpopular agendas while the people were disoriented and vulnerable. This violence and the fear it caused gradually were drilled into the collective conscience of social movements and society at large. This is how neoliberal policies became embedded in the post-coup era in Chile, paving the way for the accumulation of capital in the hands of few.

As we commemorate the 31,686 victims of the dictatorship, we also honor those whose lives were devastated by it.

We remember those who suffered torture, persecution and exile, as well as their families and loved ones, who continue to suffer beyond description. But memory should not stop at nostalgia; it should be a call to action, to question entrenched power structures, to recognize the interconnection between neocolonial dynamics and historical oppressions, and to join efforts to build a territory where all voices from the margins are finally heard.

On this 50th anniversary, it is crucial to look beyond superficial media narratives and address the systemic aspects that continue to shape our current reality.

The struggle to create spaces that foster the autonomy and sovereignty of the peoples who make up the country called Chile do not begin today, nor did they begin fifty years ago, rather it is borne of long standing anticolonial struggles. These struggles seek to honor the past, and build a present and future in which injustices are eradicated and where territories that have been silenced are able to transform the narrative, and reality itself.